The 1994 Rwanda Genocide: Causes, Timeline, Death Toll & Aftermath

1994 Rwanda Genocide: The 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda was a devastating event that unfolded over approximately 100 days from April to July 1994, resulting in the deaths of an estimated 800,000 to 1,000,000 people, primarily members of the Tutsi ethnic group, as well as moderate Hutu and others who opposed the killings.

This mass slaughter occurred amid a civil war and was orchestrated by Hutu extremists in the government, military, and civilian militias.

The genocide followed decades of ethnic tensions exacerbated by colonial policies and political instability, marking one of the most tragic chapters in modern history. Its scale shocked the world, highlighting failures in international intervention and the power of propaganda in fueling violence.

In the immediate aftermath, Rwanda faced immense challenges, including a massive refugee crisis, economic devastation, and the need for justice and reconciliation. Today, the country has made significant strides in rebuilding, with annual commemorations emphasizing prevention and unity.

Historical Background of the 1994 Rwanda Genocide

To grasp the roots of the 1994 genocide, it’s essential to examine Rwanda’s pre-colonial, colonial, and post-independence history.

Rwanda, a small landlocked country in East Africa, has long been home to three main ethnic groups: the Hutu (about 85% of the population), Tutsi (14%), and Twa (1%). These groups share a common language, Kinyarwanda, and culture, suggesting centuries of intermingling.

However, social distinctions emerged over time, with Tutsi often associated with cattle herding and elite status, while Hutu were primarily farmers. The Twa, hunter-gatherers, remained on the margins.

Pre-colonial Rwanda was organized into kingdoms, with the Kingdom of Rwanda expanding under Tutsi rulers like King Kigeli Rwabugiri in the 19th century.

Social mobility existed through intermarriage and economic ties, such as the ubuhake system where Hutu could gain cattle from Tutsi patrons in exchange for labor. Ethnic identities were fluid rather than rigid.

Colonialism dramatically altered this dynamic. Germany claimed Rwanda in 1897 as part of German East Africa, ruling indirectly through the Tutsi monarchy.

After World War I, Belgium took control under a League of Nations mandate in 1919, later a UN trust territory. Belgian administrators applied pseudo-scientific racial theories, viewing Tutsi as “superior” due to purported Hamitic origins (closer to Europeans) and Hutu as “inferior” Bantu.

In the 1930s, they introduced mandatory ethnic identity cards, solidifying divisions based on physical traits—Tutsi as tall and light-skinned, Hutu as shorter and darker-skinned. This favoritism toward Tutsi in education, administration, and the military bred resentment among the Hutu majority.

Post-World War II, global decolonization pressures and shifts in Belgian policy— influenced by the Roman Catholic Church’s support for social justice—empowered Hutu intellectuals.

In 1957, Hutu leaders issued the “Bahutu Manifesto,” demanding equality and an end to Tutsi dominance. Tensions boiled over in 1959 with the “Hutu Revolution,” sparked by rumors of a Hutu leader’s death at Tutsi hands.

Hutu mobs attacked Tutsi, killing thousands and forcing over 300,000 to flee to neighboring countries like Uganda, Burundi, and Tanzania. Belgium supported the Hutu uprising, replacing Tutsi chiefs with Hutu ones.

In 1961, a referendum abolished the monarchy, and Rwanda gained independence in 1962 as a Hutu-led republic under President Grégoire Kayibanda.

The new government institutionalized discrimination against Tutsi, with quotas limiting their access to education and jobs. Periodic violence followed, including mass killings in 1963-1964 (up to 10,000 Tutsi deaths) and 1973.

In 1973, Major General Juvénal Habyarimana, a Hutu from the north, seized power in a coup, establishing a one-party state under the National Revolutionary Movement for Development (MRND). His regime initially moderated ethnic policies but grew authoritarian, favoring northern Hutu elites.

By the late 1980s, economic pressures from falling coffee prices, overpopulation (Rwanda’s density reached 291 people per square kilometer), and a structural adjustment program exacerbated hardships.

Meanwhile, Tutsi refugees in Uganda formed the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a rebel group seeking return and political inclusion.

On October 1, 1990, the RPF invaded northern Rwanda, sparking a civil war. Habyarimana’s government responded with arrests of Tutsi civilians and anti-Tutsi propaganda, framing the invasion as a Tutsi plot to restore monarchy.

Peace talks led to the Arusha Accords in August 1993, envisioning a power-sharing government, RPF integration into the army, and refugee returns.

However, Hutu extremists opposed the deal, forming militias like the Interahamwe (“those who work together”) and Impuzamugambi (“those with a single purpose”). They stockpiled weapons, including 85 tons of machetes imported from China, and trained civilians in “self-defense.”

Propaganda outlets like the newspaper Kangura and Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM) spewed hate, referring to Tutsi as “inyenzi” (cockroaches) and calling for their extermination.

This backdrop of colonial legacies, post-independence exclusion, economic strain, and civil war set the stage for the genocide. As one UN report notes, the divisions were not ancient hatreds but constructed and manipulated for political gain.

Immediate Triggers of the 1994 Rwanda Genocide

The genocide ignited on the evening of April 6, 1994, when a plane carrying President Habyarimana and Burundian President Cyprien Ntaryamira was shot down near Kigali airport, killing all aboard.

The attack’s perpetrators remain disputed—Hutu extremists blamed the RPF to justify violence, while some investigations point to Hutu hardliners opposing the Arusha Accords. Regardless, it created a power vacuum exploited by extremists.

Within hours, the Presidential Guard and Interahamwe militias erected roadblocks in Kigali, checking identity cards to target Tutsi and moderate Hutu. On April 7, Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana, a moderate Hutu set to lead a transitional government, was assassinated along with 10 Belgian UN peacekeepers protecting her. This prompted Belgium to withdraw its troops, weakening the UN mission.

A crisis committee led by Colonel Théoneste Bagosora, a Hutu extremist, formed an interim government on April 9, with Théodore Sindikubwabo as president and Jean Kambanda as prime minister.

They declared a “final solution” to the “Tutsi problem.” Propaganda intensified, with RTLM broadcasting calls to “fill the graves” and naming specific targets. The killings spread from Kigali to rural areas, organized through local officials who distributed weapons and lists of victims.

Political power struggles were central: Hutu extremists feared losing control under the Arusha power-sharing. The recent assassination of Burundi’s first Hutu president in October 1993 had already heightened fears of Tutsi dominance. Combined with years of hate speech, these triggers unleashed systematic violence.

Timeline of Events

The genocide unfolded rapidly over about 100 days. Below is a chronological overview:

|

Date |

Key Events |

|

April 6, 1994 |

Plane carrying Presidents Habyarimana and Ntaryamira shot down. Killings begin in Kigali that night, targeting opposition leaders and Tutsi civilians. |

|

April 7, 1994 |

Prime Minister Uwilingiyimana and 10 Belgian peacekeepers assassinated. Roadblocks set up; massacres spread. RPF resumes offensive from the north. |

|

April 8-9, 1994 |

Interim Hutu extremist government formed under Bagosora’s influence. RTLM urges Hutu to “go to work” against Tutsi. |

|

April 12, 1994 |

RPF advances to Kigali outskirts. UNAMIR witnesses atrocities but is powerless. |

|

April 21, 1994 |

UN Security Council reduces UNAMIR from 2,500 to 270 troops, citing safety concerns. |

|

Late April-May 1994 |

Peak of killings; massacres in churches (e.g., Nyamata, where 10,000 died) and schools. RPF captures northern and eastern regions, ending local genocide. |

|

May 17, 1994 |

UN authorizes UNAMIR II with 5,500 troops, but deployment delays persist. |

|

June 22, 1994 |

France launches Operation Turquoise, establishing a “safe zone” in southwest Rwanda, saving some lives but criticized for protecting perpetrators. |

|

July 4, 1994 |

RPF captures Kigali; interim government flees to Zaire (now DRC). |

|

July 18-19, 1994 |

RPF takes full control; genocide ends. Transitional government installed with Pasteur Bizimungu as president and Paul Kagame as vice president. |

This timeline highlights the swift escalation and the RPF’s role in halting the violence. Estimates suggest 75% of victims died in the first six weeks.

Who Were the Victims?

The primary targets were Tutsi civilians, seen by extremists as inherent enemies due to propaganda portraying them as invaders. Moderate Hutu who opposed the killings or protected Tutsi— including politicians, journalists, and human rights activists—were also slain. Some Twa were killed, though less systematically.

The death toll is estimated at 800,000 to 1,000,000, with the Rwandan government citing over 1 million. About 70% of the Tutsi population was wiped out, leaving around 150,000-300,000 survivors.

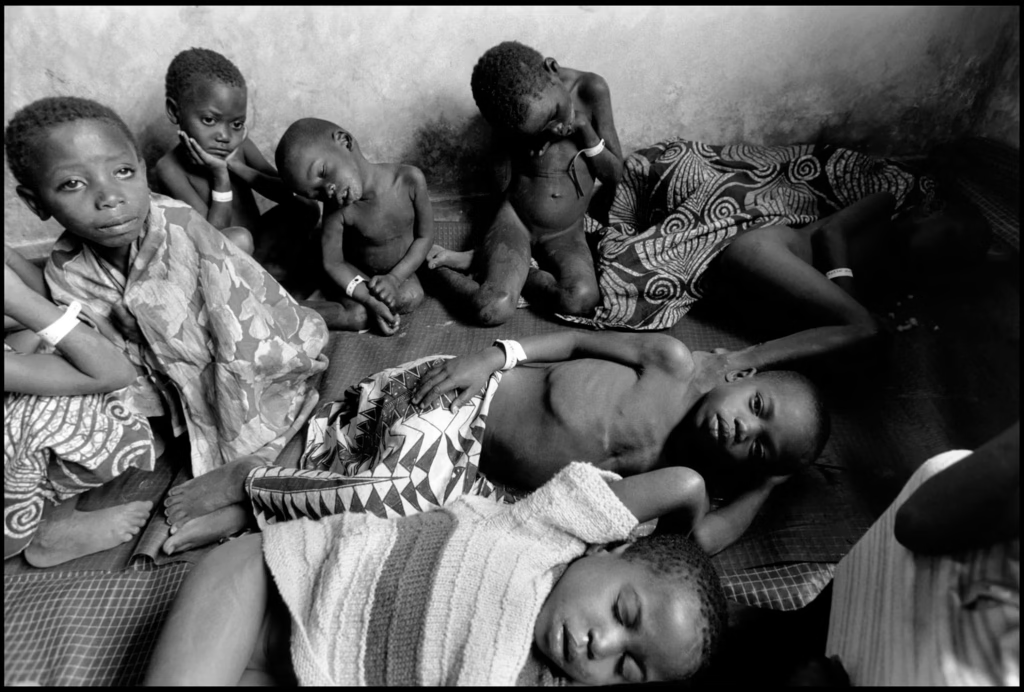

Women and children suffered disproportionately; an estimated 250,000-500,000 women were raped, many deliberately infected with HIV.

Survivors faced trauma, loss of family, and societal stigma. Orphans numbered 400,000, with 85,000 becoming heads of households.

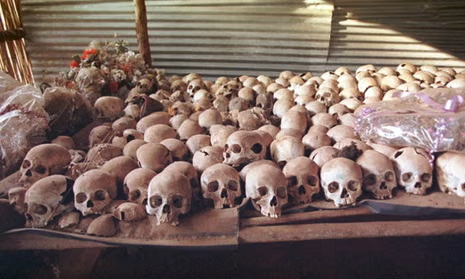

The impact extended to communities: entire families were eradicated, disrupting social structures. Mass graves and sites like churches became symbols of the horror, where people sought refuge only to be massacred.

Role of Media and Propaganda

Media was instrumental in mobilizing the genocide. RTLM, founded in 1993 by Hutu extremists, broadcast inflammatory content 24/7, dehumanizing Tutsi as “cockroaches” and urging Hutu to eliminate them. Presenters read lists of targets, coordinated attacks, and spread false rumors of Tutsi atrocities to justify violence.

Print media like Kangura published the “Hutu Ten Commandments,” promoting segregation and hatred. Propaganda drew on colonial myths, framing Tutsi as foreign oppressors.

This “hate radio” reached rural areas, inciting ordinary civilians—farmers, teachers, even clergy—to participate. Studies attribute up to 10% of the violence directly to RTLM’s influence. Post-genocide, media figures like Ferdinand Nahimana were convicted by the ICTR for incitement.

International Response (or Lack of It)

The international community’s failure is widely criticized. The UN Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR), established in 1993 with 2,500 troops under Canadian General Roméo Dallaire, had a limited mandate focused on monitoring the ceasefire, not intervening in violence. Dallaire’s January 1994 “genocide fax” warned of impending massacres and arms caches but was ignored by UN headquarters.

After the April 7 killings of Belgian soldiers, Belgium withdrew, prompting the UN to slash UNAMIR to 270 troops on April 21, effectively abandoning Rwanda. The US, scarred by Somalia, avoided the term “genocide” to evade legal obligations under the 1948 Genocide Convention. President Bill Clinton later called it his administration’s greatest regret.

France, a longtime ally of Habyarimana’s regime, evacuated expatriates but provided arms pre-genocide. Operation Turquoise in June saved lives but was accused of shielding perpetrators. African nations and the Organization of African Unity (OAU) lacked resources for intervention. Overall, warnings from human rights groups were dismissed, allowing the genocide to proceed unchecked.

How the 1994 Rwanda Genocide Ended

The genocide concluded with the military victory of the RPF, a Tutsi-led rebel force commanded by Paul Kagame. Resuming their offensive on April 7, the RPF advanced steadily, capturing northern territories by late April and Kigali on July 4. By mid-July, they controlled the country, forcing the interim government and militias to flee.

The RPF’s disciplined approach contrasted with the chaos of the extremists, though they were accused of reprisal killings against Hutu civilians (estimates: 25,000-45,000).

On July 19, a broad-based government of national unity was formed, with Hutu Pasteur Bizimungu as president and Kagame as vice president (he became president in 2000).

This ended the mass killings but triggered a humanitarian crisis as over 2 million Hutu fled to refugee camps in Zaire, Tanzania, and Burundi, fearing revenge.

Aftermath and Consequences

The genocide left Rwanda in ruins: infrastructure destroyed, economy collapsed (GDP fell 50% in 1994), and society traumatized. The refugee exodus sparked regional instability, with Hutu militias regrouping in Zaire’s camps.

In 1996, Rwanda-backed forces invaded Zaire, dismantling camps and triggering the First Congo War, which toppled Mobutu Sese Seko and led to the Second Congo War (1998-2003), causing millions of deaths.

Domestically, over 100,000 suspects crowded prisons. Health crises emerged from rapes, with thousands contracting HIV. Social rebuilding focused on unity: ethnicity was removed from ID cards, and laws banned “divisionism.”

Economic recovery was remarkable; Rwanda’s GDP growth averaged 7-8% annually from 2000-2020, driven by agriculture, tourism, and tech. However, critics note authoritarianism under Kagame, with suppressed dissent.

Justice, Trials & Accountability

Justice was pursued through multiple channels. The UN established the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) in November 1994 in Arusha, Tanzania, to prosecute high-level organizers.

It indicted 93 individuals, convicting 61, including Bagosora (life sentence, reduced to 35 years) and former Prime Minister Kambanda (life imprisonment after guilty plea). The ICTR set precedents, like convicting for genocide and rape as a genocidal tool. It closed in 2015, with appeals handled by a residual mechanism.

In Rwanda, national courts tried thousands but were overwhelmed. In 2001, the government revived gacaca courts—traditional community tribunals—to handle lower-level cases.

Over 12,000 gacaca processed 1.2 million cases by 2012, emphasizing confession, apology, and community service for reconciliation. While praised for speed and healing, they faced criticism for bias, lack of legal standards, and coerced testimonies.

Accountability extended internationally: some fugitives were tried in Belgium, France, and Canada. In 2023, financier Félicien Kabuga was arrested after decades in hiding. These efforts aimed at truth and deterrence but highlighted challenges in post-genocide justice.

Rwanda Today: Remembering the Genocide

Three decades later, Rwanda prioritizes remembrance and prevention. Kwibuka (“to remember”), the annual commemoration from April 7-13, includes national mourning, walks to unity, and educational events. The UN designated April 7 as the International Day of Reflection on the 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi.

Education integrates genocide history into curricula to foster tolerance. Policies promote “Rwandanness” over ethnic labels, with mixed success—some see progress in unity, others suppression of Hutu narratives. Memorial sites educate visitors, and Rwanda has become a model for post-conflict recovery, with women holding 61% of parliamentary seats and Kigali as a tech hub.

Challenges persist: trauma affects survivors, and regional tensions with DRC continue over militias. Yet, Rwanda’s resilience underscores the importance of reconciliation.

Genocide Memorial Sites in Rwanda

Several sites preserve the memory of the genocide, offering educational tours:

- Kigali Genocide Memorial: Burial site for 250,000 victims; exhibits on history and global genocides.

- Murambi Genocide Memorial: Former school where 50,000 were killed; preserved bodies and artifacts.

- Nyamata Church Memorial: Site of 10,000 deaths; bullet-riddled walls and victims’ clothing.

- Ntarama Church Memorial: 5,000 killed; skulls and bones displayed.

In 2023, UNESCO added four sites to its World Heritage List, recognizing their cultural significance. These attract tourists and promote education on prevention.

FAQ about the 1994 Rwanda genocide

What caused the 1994 Rwanda genocide?

Colonial divisions, post-independence discrimination, civil war, and propaganda fueled ethnic tensions, triggered by Habyarimana’s assassination.

How many people died?

Estimates range from 800,000 to 1,000,000, mostly Tutsi and moderate Hutu, over 100 days.

How long did it last?

From April 6 to July 19, 1994, approximately 100 days.

Who stopped the genocide?

The RPF, led by Paul Kagame, defeated the extremist government militarily.

How is it remembered today?

Through Kwibuka commemorations, memorials, education, and UN-designated reflection days.